|

High above the hamlet of San Martín Sacatepéquez,

a lagoon lies

in the cone of

an inactive volcano named Volcán Chicabál. Chicabál's

neighboring mountains are Siete Orejas

("Seven Ears")

and Santa Maria. I

heard about the laguna yesterday, and as is becoming more and more frequent on this journey,

picked up early this morning and went.

San Martín is about 40 minutes by bus out of Xela, which

is the ancient indigenous name for Quetzaltenango, the second largest city in Guatemala.

It sits at the bottom of a small, steep-sided valley at an elevation higher than the 2,335

meters of Xela. Farms fan up the valley's sides to forest-capped mountains, one of which

is Volcán Chicabál. Clouds scoot quickly above this landscape, getting snagged on

those green peaks.

I was the only one to get off the bus when it pulled into

the village. The driver circled and disappeared in a cloud of dust around a mountain up

the dirt road we had come down. San Martín is one of the smallest towns I have visited

and only a few locals were out and about. I approached two men standing stiffly at the

counter of a tienda and asked the way to the

Laguna Chicabál. They did not respond, and I

guessed that perhaps they did not speak Spanish. I finally found a young boy who seemed to

understand and pointed in the direction of the mountain closest to the outskirts of town.

I had heard from people back in Quetzaltenango that the trek was over two and one-half

hours straight up the side of the volcano.

Following the boy's direction, I set out down a narrow,

dirt and cobblestone lane lined with rough, uneven fences surrounding rugged houses and

well-kept gardens. Children scampered out of sight when they spotted me coming, only to

peek through shaded doorways or from behind fences. The women quickly moved indoors and

usually were not seen again. It became a game with the young ones. They would hide until I

passed by, searching for the little faces that would suddenly appear. I laughed, said,

"¡Buenos Dias!" and waved. They smiled and, more often than not, waved

back. The lane meandered between houses and gardens like a dry natural streambed and

passed through some farmland. I found the dirt and gravel road that began a steep ascent

up the side of the mountain. On the way up, houses were pitched on the precipitous land of

well-tended, green farms. Barefoot men with heavy loads of firewood on their backs

literally ran past me down the sharp decline of the road. Following the boy's direction, I set out down a narrow,

dirt and cobblestone lane lined with rough, uneven fences surrounding rugged houses and

well-kept gardens. Children scampered out of sight when they spotted me coming, only to

peek through shaded doorways or from behind fences. The women quickly moved indoors and

usually were not seen again. It became a game with the young ones. They would hide until I

passed by, searching for the little faces that would suddenly appear. I laughed, said,

"¡Buenos Dias!" and waved. They smiled and, more often than not, waved

back. The lane meandered between houses and gardens like a dry natural streambed and

passed through some farmland. I found the dirt and gravel road that began a steep ascent

up the side of the mountain. On the way up, houses were pitched on the precipitous land of

well-tended, green farms. Barefoot men with heavy loads of firewood on their backs

literally ran past me down the sharp decline of the road.

* * *

Some

of those men wore the traje (traditional clothing) of this region: a thick, unbleached wool

tunic that hangs to the knees with a slip-like undergarment hanging four inches below its

hem. The visible border of the undergarment is a brightly-colored, woven pattern in red

and blue. The tunic has short, wool sleeves, and attached half way between the shoulder

and elbow, a long, puffed sleeve. This billowy addition is the same type of woven material

as the border of the undergarment, but in different shades of red. The sleeve is gathered

at a wide wristband; finished cord-like ends are tied into a knot, closing the sleeve at

the wrist. The tunic is cinched at the waist with a very long, wide piece of cloth that is

a mixture of red and orange. This faja is wrapped around the body several times and

tied in a bow at the back. The remainder of the faja hangs down flat against the

tunic, reaching to its hem. Later I would see simply and immaculately dressed men of

obvious means who also wore shoes and hats.

* * *

The

road continued upward at a very steep grade. Dwellings thinned out and

finally became non-existent. I was alone in this sweeping tilted world of

marvelous views across the valley. Due to the increasing altitude, I stopped

more and more frequently to catch my breath. Hiking at an incessantly steep

angle, I could hear my heart pounding, laboring to deliver oxygen in the

thin air. I kept pushing myself to move on, but had to keep stopping for

thirty seconds or so to steady myself. During one of the dizzy spells that

were coming more often as I trekked higher, I began laughing, imagining

Julie Andrews singing that the hills were alive with the sound of music--only in Spanish.

By this time, the climb had been steady for nearly two

hours. Sounds of a vehicle began drifting up the road, and in another few minutes, a

four-wheel-drive truck crawled up this unbelievable grade. It came to a halt and the

driver offered a ride. I gratefully accepted, having trudged and panted almost constantly

since I left San Martín. The driver's name was Faustino and was on his way to work. This

made no sense to me as I jumped in-- where could he be going, since I had seen nothing but

rugged mountain and trees for well over an hour? The drive that took ten minutes would

have taken a very hard thirty to hike; it was the last stretch before reaching the top of

the mountain. We crested the peak and descended the other side, stopping a couple of

minutes later. Acres of sharply angled fields covered the mountainside. A few groups of

men were spread out, working down on the slopes. They looked like mountain goats on the

sideways terrain. Smiling broadly, they waved and called out their greetings. From the

road above them, we waved back, looking down across the fields. The valley far below could

not be seen and, in the distance, other mountains, checkered with farms between forested

areas, shot up into the moving clouds and sky.

I thanked Faustino and waved good-bye to the men. He said

that the top of the volcano was a little farther on. I laughed and asked what "a

little farther on" meant. He joked about it, saying, "a little farther, that's

all." I told him I live at sea level and that for me "a little farther

on" might be much more than "a little." He pointed down the road, which

headed to a tiny, shallow valley between the mountain we were on and the cone of the

volcano. Another mountain. Sweating profusely and light-headed, I continued onward,

actually peaceful and happy to be there alone. After crossing a few acres of maize fields

between the two mountains, another relentlessly steep grade began. The road narrowed to a

wide path, narrowing more and more as I reached the crest of the volcano and finally began

my descent to the lagoon. I thanked Faustino and waved good-bye to the men. He said

that the top of the volcano was a little farther on. I laughed and asked what "a

little farther on" meant. He joked about it, saying, "a little farther, that's

all." I told him I live at sea level and that for me "a little farther

on" might be much more than "a little." He pointed down the road, which

headed to a tiny, shallow valley between the mountain we were on and the cone of the

volcano. Another mountain. Sweating profusely and light-headed, I continued onward,

actually peaceful and happy to be there alone. After crossing a few acres of maize fields

between the two mountains, another relentlessly steep grade began. The road narrowed to a

wide path, narrowing more and more as I reached the crest of the volcano and finally began

my descent to the lagoon.

The path became a narrow corridor, and, at times, a tunnel

through lush trees, bushes and flowers. At one point, there was a break in the mass of

vegetation and I got my first look at Laguna Chicabál. I was awe-struck.

* * *

Last

night someone had advised that I see the lagoon in the early afternoon and

today discovered why. The lagoon is different shades of jade green,

depending on the constantly changing light. It appears to be shallow, is

over a half-mile mile wide, and is surrounded by thick forest. There are no

buildings or other signs of civilization. Clouds were stacking up in the

afternoon wind against the far edge of the volcanic cone that surrounds this

lagoon and were spilling over into the bowl. They drifted on wind drafts and

danced to the surface of the water. Then they dissipated as the air currents

subsided, only to return as breezes out on the water picked up again. The

air was still and warm from my vantage point on the opposite, sunny shore. When the clouds

tumbled over the rim of the volcano, the trees there became flat, silhouetted planes in

many shades of mint green, silver, gray, and olive green. The bright light turned the

clouds in the trees into brilliant white smoke that moved and changed the color of the

tree silhouettes. The forest became a moving montage of Japanese prints. Last

night someone had advised that I see the lagoon in the early afternoon and

today discovered why. The lagoon is different shades of jade green,

depending on the constantly changing light. It appears to be shallow, is

over a half-mile mile wide, and is surrounded by thick forest. There are no

buildings or other signs of civilization. Clouds were stacking up in the

afternoon wind against the far edge of the volcanic cone that surrounds this

lagoon and were spilling over into the bowl. They drifted on wind drafts and

danced to the surface of the water. Then they dissipated as the air currents

subsided, only to return as breezes out on the water picked up again. The

air was still and warm from my vantage point on the opposite, sunny shore. When the clouds

tumbled over the rim of the volcano, the trees there became flat, silhouetted planes in

many shades of mint green, silver, gray, and olive green. The bright light turned the

clouds in the trees into brilliant white smoke that moved and changed the color of the

tree silhouettes. The forest became a moving montage of Japanese prints.

I stayed for an hour and one-half and began my return. On

the way back up to the crest of the volcano, I stopped at a viewpoint I had seen on the

way in. I stood there for a while, dreaming and gazing hypnotically as the light

constantly changed over that huge jade medallion. Finishing off all but two frames of the

roll of film in my camera, I headed out. I had never seen anything like this and knew it

was a very significant, mystical place. Later, I was to learn that the indigenous people

hold important spiritual ceremonies here in May of each year. I was not surprised. The

bowl at the top of the world had a potent, magnetic quality that completely engulfed,

nourished, and freed me. I stayed for an hour and one-half and began my return. On

the way back up to the crest of the volcano, I stopped at a viewpoint I had seen on the

way in. I stood there for a while, dreaming and gazing hypnotically as the light

constantly changed over that huge jade medallion. Finishing off all but two frames of the

roll of film in my camera, I headed out. I had never seen anything like this and knew it

was a very significant, mystical place. Later, I was to learn that the indigenous people

hold important spiritual ceremonies here in May of each year. I was not surprised. The

bowl at the top of the world had a potent, magnetic quality that completely engulfed,

nourished, and freed me.

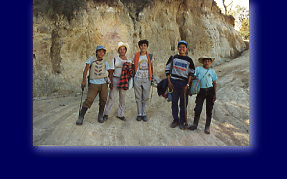

On the way down, I came across five men working the maize

field in the shallow valley between the mountain and the crest of the volcano. They called

out for me to wait for them, and I began to get nervous when I realized that no one knew I

had come here today. I eventually stopped when they began jogging toward the road,

accepting that there was nothing I could do if they wanted my camera, or watch, or

who-knows-what. We greeted each other and sheepishly I learned that they simply wanted to

walk back to San Martín with me. The friendly guys turned out to be full of beautifully

devilish humor. They asked where I was from and I told them California. One guy said,

"¿Coliflor?" (cauliflower), which we all found hysterical. This turned

into a superb game of making up many ridiculous jokes using different words in absurd

contexts.

At one point, they asked me to take

their picture. I told them I had only two more frames on my roll. They kept insisting and

finally I asked why--most likely, they would never see it, since I didn't know if I would

ever be able to return to San Martín. One grinned and simply said, "Because it's

fun!" We laughed and I consented. Not realizing until after I saw the print, we had

stopped in a curve of the road that was nothing more than an area where a bulldozer had

cut the road. In a spectacular landscape that looks like The Sound of Music goes to

Guatemala, I had taken a picture of these wonderfully boisterous campesinos in a

fairly unsightly setting. Oh well. They ended up taking a shorter route around the village

in the valley where the trek began, to the main road to catch the bus. I made it back to

San Martín Sacatepéquez in a little over half the time it had taken to climb to the

lagoon. At one point, they asked me to take

their picture. I told them I had only two more frames on my roll. They kept insisting and

finally I asked why--most likely, they would never see it, since I didn't know if I would

ever be able to return to San Martín. One grinned and simply said, "Because it's

fun!" We laughed and I consented. Not realizing until after I saw the print, we had

stopped in a curve of the road that was nothing more than an area where a bulldozer had

cut the road. In a spectacular landscape that looks like The Sound of Music goes to

Guatemala, I had taken a picture of these wonderfully boisterous campesinos in a

fairly unsightly setting. Oh well. They ended up taking a shorter route around the village

in the valley where the trek began, to the main road to catch the bus. I made it back to

San Martín Sacatepéquez in a little over half the time it had taken to climb to the

lagoon.

* * *

While waiting

for the bus to come down the road on its way to Xela, I met an old man in one of those

beautiful tunics. We sat in silence on a log for quite a while as I contemplated whether

to ask if he would allow me take his picture. I finally decided against it, thinking it a

little too invasive. Instead, I asked what language the people spoke in San Martín

because I couldn't understand it. I said it sounded like Chinese and he said, "¿De

China?"

"Yes, from China." I saw that he was having difficulty, so

offered, "It is a country across the ocean."

Uncertainly, he said slowly, "China, oh, oh yes… China."

He then let me know that the language was Mam, a Mayan dialect, and asked where I was

from. I told him I was from the United States. He then let me know that the language was Mam, a Mayan dialect, and asked where I was

from. I told him I was from the United States.

"Oh, the United States!"

"Yes. I come from a state called California."

"Hmmm."

"And the name of my city is San Francisco."

"Oh yes," he said, "We have San Francisco here."

"True," I replied, "San Francisco El Alto. They say it

is very pretty there."

"Yes, that's right."

We spoke briefly of the friendliness of the Guatemalan people and the

beauty of the country. He finally asked what language we spoke in my city. I told him that

most of the people speak English, and that many Latinos speak Spanish. I knew from how he

had responded to China that he would probably not understand the myriad of Asian languages

heard in San Francisco. I settled on saying there were also people from Japan who spoke

Japanese. He looked at me quizzically and I said, "Yes, they are from Japan."

("de Japon.")

He faltered again with uncertainty, slowly repeating, "Japon."

I felt at a loss and slightly helpless. I explained that it was another country across the

ocean.

"So you don't speak Mam in your city?"

"No," I answered carefully, "We don't have that language

in my city. This is the first time I have heard it."

He sat very still for a few moments, staring off into the distance.

Then, very gradually, he lifted his index finger in an arc to his chin, nodding slowly,

and said, "Hmmmmm."

|